DISCLAIMER: The following information is not intended, nor should it be assumed to be, a substitute for formal training in First Aid treatment and procedures. This information is presented to raise awareness of some medical conditions which can arise on canoeing, camping or hiking trips so that participants may better prepare themselves for all eventualities. The information presented is not intended to replace advice or instructions given by trained professional medical personnel. Information herein is gleened from various professional medical resources including the US Navy On-line Hospital web site, the American Red Cross web site and other reliable resources. It must be realized that improper or inadequate treatment of injuries can result in damages that sometimes are greater than doing nothing at all. Whenever possible and practical the assistance of trained, professional medical personnel should be summoned to administer treatment for serious injuries. The nature of outdoor recreation is such that injuries sometimes occur in remote areas far from available professional assistance. The information in this section is intended to be a helpful guide for treatment of injuries in such cases when getting professional help is not immediate and the nature of the injuries requires prompt attention. Marc McCord is not a trained medical practitioner, and makes no claim of expertise in treatment of injuries. Marc McCord and Southwest Paddler are not responsible for improper treatment of injuries and resulting damages that may occur. DISCLAIMER: The following information is not intended, nor should it be assumed to be, a substitute for formal training in First Aid treatment and procedures. This information is presented to raise awareness of some medical conditions which can arise on canoeing, camping or hiking trips so that participants may better prepare themselves for all eventualities. The information presented is not intended to replace advice or instructions given by trained professional medical personnel.

Each year, about 9,000 people are bitten by poisonous snakes in the U.S. Only about 15-25% actually receive venom, and U.S. deaths from snakebites only total about ten or fewer people annually. In 2002, there were only 9 snakebite deaths in the US. Yet, snakebites are one of the most feared of the problems that can confront paddlers, hikers, campers and others who enjoy the outdoors. Most snakebite deaths occur in small, young children whose lack of body mass and immune system development make them more susceptible to snake venom. However, a far larger number of people suffer medical complications ranging from mild to serious problems from improper treatment than the number who die. Therefore, knowing what to do to avoid snakebites and how to properly treat them if they occur is critical to preventing permanent injury or death.

Venomous Snakes of the U.S.

|

Cottonmouth Water Mocassin |

Southern Copperhead |

Copperhead |

Broadbanded Copperhead |

|

The most serious complication from improper snakebite treatment is amputation of a foot, leg, hand or arm, the parts of the body where most snakebites are most commonly received. If you have a snakebite kit, then THROW IT AWAY! According to the American Medical Association, snakebite kits are useless at best and dangerous at worst. Since most people do not have serious long-term complications from snakebites it is generally best to seek professional medical help as soon as possible after a bite. The only acknowledged practical field treatment of a poisonous snakebite is use of a Sawyer Extractor, but it must be used within 30 minutes of the bite to be effective. By the very nature of paddlesports, getting professional help may be many hours, or even days, away. Therefore, field treatment may be necessary and paddlers should know how to properly administer the type of treatment that will prevent serious complications. A good place to start is by knowing about snakes and snakebites.

In the U.S. there are about 20 species of poisonous snakes belonging to four families and two groupings. The most common group includes the families of rattlesnakes, copperheads and water moccasins, snakes commonly referred to as "pit vipers" because of the heat-sensing pits located near their eyes and used to detect warm-blooded creatures and direct strikes to their targets. This group of snakes produces "hemotoxic" poisons that work by invading the lymphatic stream to reach the hearts of victims. The most common snakes of this group are the various species of the rattlesnake family, but the ones most commonly encountered by paddlers are water moccasins, also known as "cottonmouth" water moccasins because of the white color of their inner mouths. Copperheads are the least commonly encountered. All are excellent swimmers and tree climbers.

Venomous Snakes of the U.S.

|

Diamondback Rattlesnake |

Western Diamondback Rattlesnake |

Timber Rattlesnake |

Northern Blacktailed Rattlesnake |

|

It is important to realize that all these snakes are very timid, and will avoid human contact whenever possible. Most snakebites occur when stepping on or attempting to handle snakes. Water moccasins are very curious, but they tend to flee once they realize that their presence is detected. Many bites from rattlers and copperheads occur from people lifting wood, rocks or other ground cover under which the snakes are taking shelter from the sun. Turning ground cover with a stick, pole or other long object should always be done prior to lifting when in snake country. Gathering firewood at night is highly inadvisable. Walking barefoot, walking in the dark at night, placing hands or feet where snakes may be resting and stepping over, rather than on, logs are common ways of getting bitten. Unless your name is Steve Irwin, and you hail from Australia, do NOT attempt to handle snakes. And, do not indiscriminately kill them either - snakes serve a very significant purpose in the ecosystem and are more useful in killing and eliminating disease-plagued rodents than they are harmful to humans.

On and around rivers the most commonly encountered snakes are the poisonous water moccasin and the non-poisonous watersnakes. Water moccasins tend to be colored charcoal grey, black or dark brown, with yellowish-white bellies and a white inner mouth. Like all pit vipers, they have vertical slit eyeballs and triangular heads. Their bodies are generally thin, with an adult length of 3-4 feet, though they may be larger and longer on some occasions. Water moccasins are seldom found on cold-water rivers, though that is not a hard and fast rule. They will usually be seen from late spring to early fall, and become very inactive in cold weather.

Venomous Snakes of the U.S.

|

Grand Canyon Pink Rattlesnake |

Prairie Rattlesnake |

Mojave Rattlesnake |

Midget Faded Rattlesnake |

|

Of all the various species of watersnakes, the only one that really poses any threat to paddlers is the diamondback watersnake, which strongly resembles the poisonous diamondback rattlesnake. Watersnakes have round eyeballs, thick bodies, and may reach lengths of 5-6 feet or more. While water moccasins tend to swim completely on the surface of the water a diamondback watersnake will probably have nothing but its head above water. Its body mass is too great to be supported by the surface tension of water. Also, watersnakes primarily feed on fish, crawdads and other creatures found underwater, so they spend most of their time beneath the surface, coming up mainly for a breath of fresh air. Unlike other species of watersnakes, the diamondback watersnake is both curious and aggressive. Even though it has no venom it is loaded with bacteria, germs and pathogens that can cause serious damage from bites. In fact, the damage from a non-poisonous diamondback watersnake is frequently far more serious than that of a poisonous water moccasin, and may result in an amputation of a limb or other serious dermal injuries. Their sharp teeth will bite many times in rapid succession, tearing skin and infecting open wounds with enough bacteria and other contaminants to produce serious injury. Do NOT play with diamondback watersnakes!

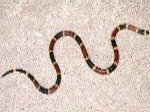

The second group of snakes found in the U.S. is the family of coral snakes, a relative of cobras, adders and mambas. These snakes have round eyes, rounded heads, and neurotoxic poison that directly attacks the central nervous system resulting in interruption of lung, heart and other organ functions leading to paralysis and/or death. Coral snakes have no fangs, and must chew to inject venom. For that reason most adults are not candidates for coral snake bites. Coral snakes are very rare, and most injuries from them are caused by handling, where they can bite on the soft tissue of fingers, hands or the areas between fingers, feet, toes or the soft tissue between toes. Because of the small size of coral snake heads they cannot open their mouths wide enough to bite on large surface areas, nor would their teeth be likely to penetrate tough skin. Coral snakes bear a very strong resemblance to the much larger and non-poisonous kingsnakes. Both have alternating bands of red, black and yellow with black heads. The easiest way to tell the difference is the sequence of color bands. Remember this - Red touches black is a friend of Jack; red touches yellow kills a fellow. Coral snakes are found almost exclusively in the southern and southeastern U.S, while pit vipers may be found in almost any state except Alaska, Hawaii and Maine.

Venomous Snakes of the U.S.

|

|

Coral Snake |

Texas Coral Snake |

|

|

There are actions that can be taken to treat poisonous snakebites while getting a victim to professional medical treatment. Whenever possible, these should be administered enroute to a hospital or other professional help. However, at times it may be necessary to provide as much treatment in the field as possible due to remoteness and distance from (or time required to get to) professional assistance. Help can usually be found at hospitals, ranger stations, fire stations with EMS services, doctors' offices or similar places. Field treatment is only helpful when done properly, and administering treatment improperly may result in serious injury or death to the victim. The main points to remember are these: Apply a splint and sling, if possible, and transport the victim to professional medical attention as quickly as possible. There are very few effective measures that can be taken by a layman in the field, and most actions taken will increase the damage from the snakebite injury. In the case of a pit viper bite in the United States, do NOT apply ANYTHING that in any way impedes blood flow and circulation. Such actions often result in severe dermal necrosis (tissue death in the contricted area where poison is trapped.) Below are some Do's and Don'ts for treating snakebites:

Non-Venomous Snakes of the U.S.

|

Diamondback Watersnake |

Diamondback Watersnake |

Broadbanded Watersnake |

Plainbelly Watersnake |

|

| Things to Do |

Things NOT to Do |

| Move victim, and everybody else, away from snakes; |

Do not cut and suck the wound, either manually or orally; |

| Identify the snake - kill it ONLY if necessary; |

Do not apply a tight, narrow band tournaquet - these cause amputations!; |

| Lie the victim down with the bite area at or just slightly below the heart level; |

Do not apply ice or heat packs, and do not use a stun gun on the bite area; |

| Calm the victim by explaining the facts about snakebites; |

Do not give the victim any food or drink, and this applies especially to alcohol!; |

| Immobilize the bite area with a splint and sling, if possible; |

Do not allow the victim to become alarmed, excited or agitated, as this will only increase blood flow and the chances of getting poison to the heart; |

| Remove constricting jewelry or clothing unless the victim resists; |

Do not allow victim to exercise vigorously, including running; |

| Get professional medical help as quickly as possible. |

If you must kill the snake, then do NOT touch its head for at least one hour. If you must kill a snake for identification purposes, then completely remove its head and bury it. Snake heads have been documented as capable of biting and injecting poison an hour or more after decapitation; |

| |

Do not waste valuable time on unimportant acts like trying to find a snake to identify or kill it. Hemotoxic poison will start to enter the blood stream within 30 minutes, and neurotoxic poison works even faster. |

Following the above protocols will greatly reduce the chances of serious complications from snakebites. Bear in mind that few people die from poisonous snakebites and the vast majority of snakebite victims are not even venomized. Snakes generally reserve their venom for prey they intend to eat. If you encounter a snake that can eat you, then you have a much bigger problem than poisoning! No such snakes exist, especially in the U.S. Above all else, DO NOT PANIC! Snakebites are more a nuisance than a serious medical problem in most cases, and in the other cases panic will merely result in a loss of efficiency in getting a victim to professional treatment, which may result in serious injury or death.

A personal word about snakes from the author of this web site - I have been paddling rivers since 1975, and in all those years and many thousands of miles, have not seen more than perhaps 50 snakes. Never have I had a close encounter with one, and I have not come close to being bitten. I have only heard about a couple of people who have been snakebitten while paddling. The purpose of this treatise is not to inject fear about paddling into anyone, but rather to provide information about what to do in the rare circumstance where a snakebite does occur. It is far better to be prepared and never need this information than it is to need it and not be prepared. Forewarned is forearmed!

All snake photos on this web site, except the second photo of the Diamondback Watersnake which was taken by Chip Ruthven, are used with the permission of David Roberts, who is one of the world's leading authorities on snakes and snakebites, as well as bites and stings of spiders and scorpions. Most of the information regarding snakebite prevention and treatment was also provided by David, and I want to express my "undying" gratitude for his contributions on behalf of all paddlers, campers, hikers and others who enjoy outdoors activities.